First Impressions

Autism advocacy doesn’t always start with a grand gesture. Sometimes, it begins with a simple story, like learning to design accessible charts for a colorblind professor. This candid reflection explores what true inclusion looks like and why meaningful change is about consistent, small actions.

A ride in the Wayback Machine to my first attempt at autism advocacy

Author’s note:

I first posted to LinkedIn some time in late 2015 or early 2016. The post was an invitation to a joint social event for members of the Michigan chapter of the American Medical Writers Association and the Michigan chapter of The Society for Technical Communication.

In retrospect, it wasn’t the sort of thing that should be posted to LinkedIn. At least not by someone who had a follower count that barely cracked the double digits. Fortunately we had other ways to publicize the event. And the event was lovely, by the way.

The second time I ever posted to LinkedIn was in early March, 2024. Here is the post in its entirety:

A reminder to everyone in the US that Monday, March 11 is National Napping Day. This occurs every year on the Monday following the change to Daylight Saving Time.

Join me in scheduling an "important meeting" for mid-afternoon tomorrow and help celebrate this most important of holidays.

I’m not entirely sure why I felt the need to proclaim my fondness for naps, but the post seemed to resonate with the 2 people who commented on it. So there’s that.

Post number 3 and post number 4 were to acknowledge “Neurodiversity Celebration Week,” which was March 18th through the 24th. Post number 3 marks the first time I disclosed my autism in a public forum (online or elsewhere).

A handful of people knew that I am autistic. I had not planned on disclosing to those people, but circumstances forced my hand. That’s a story for another day. I decided that if 5 people knew, it was only a matter before 500 knew, so I might as well take control of the narrative and tell people on my own terms.

Here, for your amusement and bemusement, is my first-ever attempt at autism advocacy. I’ve resisted the urge to revise it and have presented it as it was first published.

Thoughts on Neurodiversity Celebration Week, Part 1

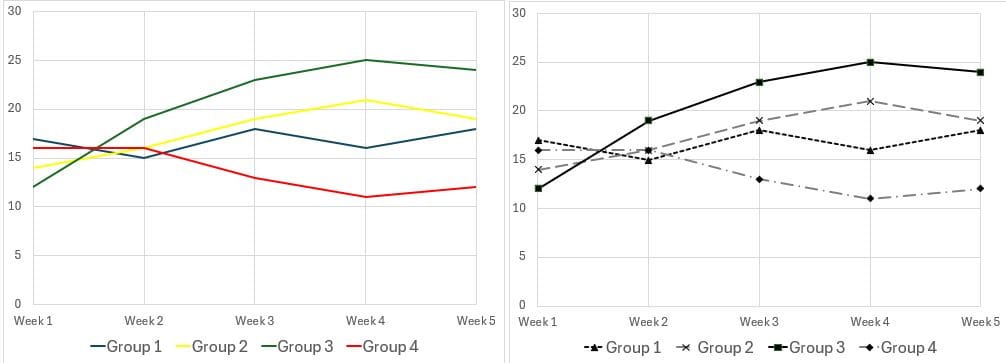

I was in college 30+ years ago, and I needed to give a presentation for a class. One of the graduate students in the department took me aside and told me that any graphs or charts I presented should be in black and white, using different line patterns (solid, dotted, dashed), different markers (squares, circles, triangles), and different shading to distinguish between the groups. This was because one of the senior faculty, Dr. H, was colorblind. It was easier for him to read graphs that were in black and white.

And so I made the graphs and charts in black and white. We didn’t call it an accommodation. We didn’t call it anything because we didn’t need to talk about it. If making the graphs in black and white would help Dr. H, so be it. No discussion required.

Nobody treated Dr. H like he was broken or defective. Nobody misunderstood his colorblindness and tried to give him a white cane or a seeing-eye dog or books written in braille. Nobody felt sorry for him or excluded him from anything. Nobody felt the need to be careful about discussing certain topics around him.

Nobody made Dr. H go to an optometrist or ophthalmologist to get proof that he was colorblind. There were no forms. If anyone from HR or the legal department knew that Dr. H was colorblind, they didn’t care.

This is NOT an appeal to return to the mythical “good old days.” And I realize that there are significant differences between being colorblind and being neurodivergent. And I realize that the issues of disability and access are complicated. I’ve lived the realities of being autistic in corporate America.

But at the same time, we were told that a small change would make life easier for Dr. H. So we changed. And we all internalized that change. You could always spot someone who came out of that particular program because of the way they made charts and graphs. To this day, I still think about Dr. H whenever I am making charts or graphs.

Inclusion and diversity aren’t about an annual Grand Gesture. Or proclaiming a Day or a Week. Or certificates or plaques or speeches or any of the other stuff that’s easy and showy. It’s about recognizing an opportunity to make somebody’s life easier or better. And making a change. And internalizing that change. And then looking for the next opportunity. It’s a long, slow process that isn’t particularly glamorous. And it’s not as easy as a social media post professing support. But it’s how change happens.

I don’t want a certificate or a T-shirt or a social media post or a pizza party or anything else from “The Big Book of 101 Empty Corporate Gestures.” I just want the freedom to be myself. I want the same courtesy that a bunch of clueless college students automatically extended to Dr. H 30+ years ago. I want change.

In response to this post, a colleague of mine said that she “definitely would love to learn more about how to make it easier and better for neurodiverse people to thrive at work.”

I didn’t have much of an answer, so I responded with this:

If I had a single, magical, "one size fits all" answer, I'd be more than happy to share. Autism is complicated. There are at least 100 different genes associated with autism, and some put that number closer to 200. Developmental factors and other issues are hard to study. Due in part to the fact that nobody can seem to agree on a definition of autism. What helps one person may not help the next.

I know it sounds like a cliche, but the first step is to ask the question "how can I make your life better?" It doesn't have to be a direct question, or a profound conversation. Throw out options. "Would you rather call me or discuss this by email?" Little things matter. I'm not asking to be King of the World. I'm just asking that when I say "I need a minute to think about that," you give me some time to think. (Not you personally. "You" in the global, generic sense.)

There are plenty of articles circulating this week about how to interact with autistic co-workers. Some of them are even accurate. Take a look at a few. See what makes sense. Keep in mind that there are probably a lot more people around you who are neurodivergent than you realize.